Craig invited me to join him and Jeff on this two-day mountaineering adventure in the Palisades when another climber was unable to make it. I was immediately interested and also incredibly nervous since the two climbs are very technical. Reaching Balcony and Disappointment peaks requires crossing a glacier and its burgschrund followed by a fair amount of class 3/4 climbing, and the route to Palisade Crest includes plenty of exposed class 3, 4, and 5 terrain. I swallowed my inhibitions, trusting Craig and Jeff’s expertise, and accepted the invitation. I’m glad I did – these climbs are some of the most difficult I’ve ever attempted but the reaching the peaks was sweeter as a result!

Trip Planning

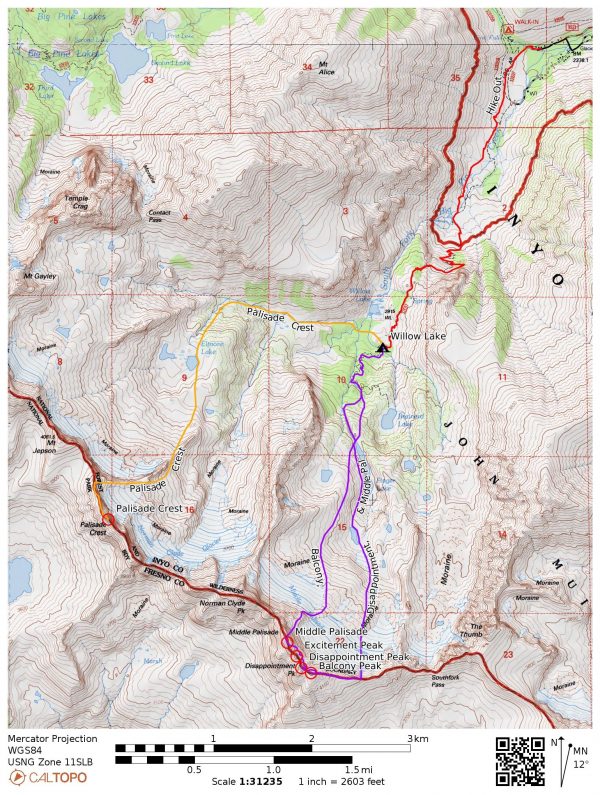

Specs: 18.1 mi | +/- 11,800 ft | 2 days, 1 night

Difficulty: The difficulty spans the entire range from class 1 to class 5; see the route descriptions below for specifics [learn more]

Location: Inyo National Forest, California | Home of Eastern Mono/Monache and Northern Paiute peoples | View on Map

Route: The route to any of these peaks begins at the Big Pine Creek Trailhead. Follow signs for the south fork trail which, after several miles of walking and a few thousand feet of elevation gain, leads you to a forest where the trail splits in two directions. One path leads to Willow Lake and the other to Brainard Lake. We set up camp near this junction since we went both directions.

- Approach to Balcony Peak [Class 2] – Take the path toward Brainard Lake until you pass a pond near the highest part of the trail. Leave the trail here and head south to Finger Lake. There are several use trails and cairns if you can find them; we simply scrambled up the Finger Lake outlet creek. Traverse around Finger Lake on the west side, moving from bench to bench with the goal of reaching the far end of the lake. From the head of Finger Lake, continue uphill to a charming tarn and then further up through horribly loose talus and scree to the base of the Middle Palisade Glacier.

- Climb to Balcony [Class 3] – Hike up the Middle Palisade Glacier (crampons and an ice axe are helpful or even necessary depending on conditions) to a chute that leads to the Sierra Crest. Bob Burd describes this chute as the “rightmost of the four snow-filled chutes on the left side of the ridge.” It can be difficult to cross the bergschrund late in the season – we just barely made it by shimmying up an icy chimney. Scramble up the extraordinarily loose chute to the crest and then climb the class 2 ridge to Balcony Peak.

- Traverse to Disappointment Peak [Class 3 – 4] – Backtrack down the Sierra Crest, losing about 300 feet, and then begin traversing across the north face of the mountains, tricky terrain composed of chutes (or gullies, depending on your definitions) and arêtes. There are a few cairns marking notches in the arêtes where you can scramble up and over into the next gully, but many crossings are not marked. Most of this terrain is class 3, but there are some class 4 problems along the way. Once you reach the chute that leads to the notch between Balcony and Disappointment (“Doug’s Chute”), scramble up to the Sierra Crest and then follow the ridge to the summit.

- Traverse to Middle Palisade [Class 3 – 4] – Backtrack down the Sierra Crest a little ways until you can drop down onto the north face, just like for the traverse from Balcony to Disappointment. You’ll again be crossing class 3 – 4 terrain between chutes and arêtes. There doesn’t appear to be any one way to navigate this difficult area; we were forced to downclimb and then ascend in several of the half-dozen chutes. You eventually reach a chute that offers access to the Sierra Crest very near Middle Palisade; scramble up to reach the summit.

- Descent from Middle Palisade [Class 3] – Traverse the ridge to the south for a few tens of feet until you can drop down onto the northeast face via some class 3/4 terrain. Then trend north, descending through the obvious chute and staying to skier’s left of a fin near the bottom of the slope. Just below the fin, turn right and descend through a steep chute composed of sharp red and white rocks. Continue hiking east-northeast on the loose slopes just above the Middle Palisade Glacier (there is a faint use trail) until you can safely descend on horribly loose glacial till. The rest of the trek to Finger Lake is fairly straightforward class 2 cross-country hiking. There are cairns on the slabby plateau above Finger Lake that lead to the foot of the lake.

- Approach to Palisade Crest [Class 2] – Take the path toward Willow Lake, following cairns north for a few hundred yards and then west across a meadow and three different creeks. Continue following the cairns up the South Fork of Big Pine Creek, staying mostly on its south side except for a particularly willow-choked meadow which is most easily passed on the north side of the creek. A little higher up, follow the outlet creek (the cairns stay a bit south of the creek) up to Elinore Lake.

- Climb to Palisade Crest [Class 4 – 5] – Traverse around Elinore Lake on its eastern side and climb south towards the obvious ridge, aiming for a large notch at about 11,900 ft. Cross to the southeast side the ridge at the notch and continue upwards, remaining near the foot of the ridge and well above the Norman Clyde Glacier until you reach the Sierra Crest at “Scimitar Pass.” (It’s not really a pass, just a point on the crest.) Follow the crest of the ridge, occasionally dropping down a few feet on the southwest side, until you arrive at a steep south-facing slope leading directly down to the large notch between the ridge and Palisade Crest. I would describe the first half of the ridge traverse as easy (but sometimes exposed) class 3 climbing and the second half as a mixture of class 3 and class 4 (frequently exposed) terrain. We found a sling and rappel rings at the top of the slope above the notch and rappelled down, but others have followed a class 4 line with very careful route finding. Cross the notch and scramble up to a small ledge below the obvious crack-covered ramp. It’s pretty steep (50 deg from horizontal) but the cracks are frequent and deep enough to be excellent holds. Secor rates this 160-ft (48 m) slope as class 4, which seems accurate. I appreciated a rope since the climb is very exposed (there is a set of rappel rings at the top of the slope). From the top of the slope, scramble up some class 3/4 rock to the summit.

Permits & Regulations: Permits are required for all overnight trips in Inyo National Forest and you must store your food in a way that prevents bears or other animals from getting to it. As always, practice leave-no-trace when you’re out in this beautiful wilderness!

Resources: The South Fork of Big Pine Creek page includes lots of useful information – check the sidebar for current Forest Service alerts and closures. Since these routes cross several large creeks and a glacier, I recommend getting as much information about current conditions as you can, e.g., via trip reports on PeakBagger.com. Also, pay close attention to the weather forecast! These climbs are technical and exposed to the elements; you do not want to get caught in a storm up there.

Balcony, Disappointment, and Middle Palisade

21 Aug, 2021 | 8.9 mi | +7100 / -5300 ft | View on Map

Craig and I set off from the overnight parking lot at 5:00 AM, trudging along the road to the trailhead under the light of our headlamps. It only takes about 15 minutes to reach the trail, which remains fairly level for a while. A full moon illuminates the landscape around us as we hike and we pass two fellow early-morning hikers carrying day packs helmets a short distance down the trail. We reach the South Fork of Big Pine Creek a little while later and look around for a “good” crossing before committing hopping between some barely-dry rocks.

Past the creek, the trail begins climbing a series of gentle switchbacks. There’s enough light now that headlamps are no longer necessary, so I click it off to preserve the battery. Even with the increasingly bright sky, the scenery remains partially obscured in a smoky haze. I can smell it in the air and it irritates my throat and lungs a little, so I pull a buff over my mouth and nose to filter it out; the makeshift mask is only partially effective.

I try to stay ahead of the day hikers we passed earlier, but they catch up pretty quickly once we begin ascending in earnest (we have overnight backpacks, after all) so Craig and I let them pass by. We still maintain a speedy pace as we continue hiking behind them, maybe even too speedy since my legs are burning by the time we level out on a bench overlooking Willow Lake. The Palisades glow red and orange in the early morning sun, a beautiful sight that makes the pre-dawn start entirely worthwhile!

A short descent leads us to a trail junction: the left branch heads toward Brainerd Lake and the right branch doubles back to Willow Lake. We’ll be heading both directions this weekend, so this will be our base camp. We find a nice campsite amidst scattered pine trees and granite slabs a short distance from the trail and hurriedly shuffle the gear we’ll need for the climb today into our day packs, stashing the overnight gear behind a large boulder.

Once we’ve got our gear all sorted, we return to the trail and head toward Brainerd Lake. Hiking without the heavy overnight gear feels amazing and we speed up the path, winding up switchbacks beside the roaring Finger Lake outlet creek. When the trail levels out beside a small pond we begin bushwhacking through some willows and then uphill through the forest toward Finger Lake. We don’t see many cairns to lead the way and head over to the outlet creek. The rocky chute proves to be a perfectly good route up to the lake, although we’re forced to cross the creek on wet, slippery rocks a few times.

The sunlight is just barely illuminating the western bank of Finger Lake as we emerge from the chute at about 7:50. It’s a beautiful spot and we take a break on the shore to eat a snack and filter water. Only minutes later, the two day hikers we met this morning appear on the opposite bank. I think we’re all surprised to see each other again since they were ahead of us! We chat for a few minutes and learn that they’re climbing Middle Palisade, one of the peaks we’re attempting to climb today as well.

After a short break, Craig and I head out, scrambling up the western bank of Finger Lake. A series of cairns lead to a network of slabs, cliffs, and benches that overlook the lake. We find two abandoned beer cans (still full!) along the way and mark their location so we can pick them up if we pass this way on our return journey. The route finding gets a little tricky as we contour above the lake, mostly because it’s difficult to predict if a bench will lead to other benches or end abruptly at a cliff. Even so, we quickly navigate across to the far side of the lake and manage to avoid loosing any elevation. Craig leads the way up a grassy chute with some fun class 3/4 chimney problems; I jokingly grumble about his “tall person beta” as he easily pulls himself up and over a chockstone but quickly find my own route up the chute.

Above the chute, I enjoy a cross country stroll through grass and occasional boulders to a pristine, bright teal tarn. We take another quick break here to refill our water bottles and then continue onward. From the head of the tarn, we scramble up increasingly loose talus, scree, and glacial till until we reach the foot of the Middle Palisade Glacier. From a distance, the slope looks like a pile of rocks but closer inspection reveals that the gravel and boulders are embedded in thick, concrete-like ice. We pick our way up the ice-rock matrix and eventually don crampons when the slope steepens. I’m not sure they’re entirely necessary, but they’re certainly more grippy than my shoes! I carry my ice axe in self-arrest position, occasionally using it like an ice tool to pull myself up the slope.

When Craig and I arrive at the base of the chute that will supposedly lead up to the Sierra Crest, we’re dismayed to find a wall of solid ice with a dark, gaping burgschrund on either side. There’s absolutely no chance we can climb the ice face; it’s too hard and too high to attempt without ice tools, ice screws, and a rope. Our only hope is a dirty chimney where the ice flow has separated from the wall of the chute, and it doesn’t look fantastic. The first five or six feet of the chimney are composed of the same smooth, impenetrable ice, so we’ll have to rely on good foot placement and our crampons to stem up. To make things even more spicy, the ground disappears into the black depths of the bergschrund just feet away.

We contemplate our options for a minute or two. Climbing up the chimney will commit us to the the traverse over to Middle Palisade; we are not going to down-climb this feature. There don’t appear to be any other routes to the Sierra Crest – everything else is either blocked by the bergschrund or is a class 5 cliff – so our only other option is to turn around and go back to camp. I try to weigh the risks objectively but I don’t like the thought of giving up and cast my vote for attempting the ice chimney. Craig agrees and steps back to give me room to get into the chimney.

After a few deep breaths, I begin stemming up the ice and try not to think about the dark crevasse below. There’s not much to hold on to besides small, smooth features in the ice and they are very cold. Thankfully, my crampons stick to the ice and I’m quickly in a safer spot wedged between the ice and the rock. I struggle for several minutes to wiggle myself up between the two walls but then I’m free, standing on a small, rocky outcropping above the chimney! I take a good look at the chute above – it’s mostly ice, but lower angle and the sides of the chute are rocky, so we’ll be able to make it up. I call down to Craig that we’re a go and he begins the climb.

Craig struggles a little more than I did with the narrow, top half of the chimney (being shorter has its advantages!) but pushes through and reaches the top. We carefully scramble up the side of the chute and abandon the ice as soon as we can for rockier terrain. It’s all horrendously loose but we have no choice but to continue upward. We find sturdier footing a little higher up the chute and reach the Sierra Crest by 11:00, extremely grateful to be back on class 2 talus.

After a brief rest, we scramble up the ridge to Balcony Peak, arriving at 11:35. We sign the summit register and then stare across the ridge at the other peaks on the list for today. Disappointment Peak lies only a few hundred feet away. Excitement Peak is just past Disappointment, with Middle Palisade rising behind them both. The quickest way between the peaks requires navigating a series of class 5 notches; there’s even a rappel station just below Balcony Peak! However, we didn’t bring a rope today so we’re going to have to traverse across the steep northeast face of the mountain.

Craig and I backtrack, descending a few hundred vertical feet until we find a spot where we can drop down onto the face. There appear to be many routes across the face; you can string together any number of slabs and ledges. The chief difficulty is finding spots where you can cross the series of arêtes and ribs that run vertically down the mountain. We pick a passable-looking notch in the closes arête, then carefully navigate across the 3rd and occasionally 4th class rock and peer across into the next gully. More often than not, the path between subsequent notches is a bit of a roller coaster, dropping a ways before climbing back up to the next one.

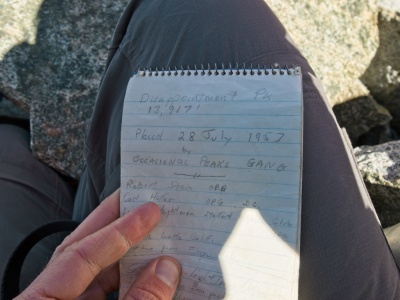

After crossing several gullies and arêtes, we reach “Doug’s Chute” which leads up to the notch between Balcony and Disappointment Peaks. So we scramble on up to just below the crest and then ascend about 10-15 feet of class 4 rock on climber’s right to reach the crest. After some searching we find a route around the left side of the crest composed mostly of class 3 terrain with a little class 4 thrown in. Finally, at 13:40, two full hours after leaving Balcony Peak, Craig and I reach Disappointment Peak. It’s high time for a rest, so we pull on jackets and peruse the 64 year-old summit register.

Although we’re both very tired, Craig and I don’t stay atop Disappointment Peak for long. We have a lot of climbing left to do and only five and a half hours of daylight left. Neither of us want to be up on the mountain when the sun sets. So we backtrack a bit, back down to the northeast face of the mountain, and resume the traverse, navigating through more gullies and over more ribs. The constant concentration on safe climbing and the mental energy required for route finding is exhausting. I find myself looking longingly at the glacier below, wanting nothing more than to be on flatter, less complicated ground.

Several hours later we reach a series of gullies directly below Middle Palisade and start trending upwards rather than focusing on horizontal travel. The climbing becomes a little easier, particularly once we reach the Sierra Crest. We reach summit at 16:35, three hours after leaving Disappointment Peak. I can’t even express how happy I am to spot the silver summit register box! We take a break to sign the register and admire the views. The smoke seems to have thinned a bit, but the visibility still isn’t great; the Owens Valley is still completely obscured. I munch on some trail mix, careful to save some for the descent. I didn’t expect to be so far from camp this late in the day, and it’s all the food I have left in my pack.

The descent from Middle Palisade goes quickly and smoothly. It’s a simple route: scramble down the class 3 gully to the base of the mountain and then hook a right to descend another gully that empties out onto the moraine. By the time we reach the foot of Middle Palisade, the sun has sunk behind the Sierra Crest and we’re left in shadow. Hiking down the moraine proves to be the most frustrating part of the entire day: every step results in a rock slide, sometimes dislodging rocks big enough to crush a hand or foot! Craig remarks that his previous climb occurred earlier in the season when the moraine was covered in snow, making for much easier travel.

After what feels like an hour of loose till, scree, and talus, we finally reach the solid slabs above Finger Lake. A series of cairns lead us back to the water’s edge where we find several groups of campers. Our own campsite is still quite a bit further, so we hurry onward as the sky darkens. The cairns continue down toward Brainerd Lake but we lose them as darkness falls. I struggle to maintain my composure as we push through thick willows, searching for the trail with only headlamps to light the way.

Our good luck prevails and we soon stumble upon the trail. Craig and I hike as quickly as we can down the switchbacks to the trail junction and arrive at our stashed backpacks at 20:45. We’ve been on the move with only the occasional break for nearly 16 hours, and we’re both exhausted. My legs ache, my arms and shoulders are tired from the climbing, and all I want to do is sleep for the next 12 hours. We set up camp in silence and I eat some food even though my appetite is mostly gone. Both Craig and I are independently contemplating bailing on the climb tomorrow, but don’t mention it to each other as we set our alarms for 5:00.

Palisade Crest

22 Aug, 2021 | 9.2 mi | +4700 / -6500 ft | View on Map

Seven hours of sleep works wonders! I feel much better than I did last night. Jeff will be joining us today, but he’s starting from the trailhead and our plan is to meet up at Elinore Lake. Craig and I leave camp at about 5:40, heading west toward a network of creeks that drain into Willow Lake. We cross two of them but are stymied at the third. It appears the only way across is through the water. I don’t really feel like getting my shoes wet, so I take them off and wade through the water to the opposite shore. Craig follows suit. As we’re lacing up our shoes on the opposite bank, Jeff appears on the other side of the creek!

We set out together and I get to know Jeff a little bit since I’m just meeting him today. We follow a winding use trail through meadows and forests, eventually ending up hopping between rocks on the northern side of the creek. It’s a bit tedious, but I’m just happy to be on class 2 terrain after spending 8+ hours on class 3 and 4 terrain yesterday.

After a bit of an uphill climb, we reach Elinore Lake at 7:30. The water is perfectly still and reflects the Palisades like a mirror. We sit for a while, snacking, chatting, and refilling our water bottles – this is the last reliable water source so I drink as much as I can before topping off my bottles.

From the foot of Elinore Lake, we contour around the southern side and climb up about a thousand feet of slabs, grassy ramps, and solid talus to an enormous rocky fin protruding from the ridge. Staying high, we continue scrambling up increasingly loose talus and scree until we’re able to climb up onto the ridge itself where the rock is a little more stable. In what feels like no time at all (9:45, only four hours from camp!), we reach “Scimitar Pass,” a point (not really a pass) on the Sierra Crest marked by a massive cairn.

Our next goal is to traverse the ridge and reach the notch just below Gandalf Peak, the highest pinnacle on the Palisade Crest massif. (All of the Palisade Crest summits are supposedly named after Tolkien characters, but I cannot find a definitive source!) The exact route to reach the notch seems to vary depending on who you ask. Secor describes a line that remains on top of the ridge until just above the notch, but others report a descent from the ridge to the northeast face with a class 4 traverse across the face. We decide to stick to the very top of the ridge for as long as possible since the northeast face looks treacherous.

At first, we scramble up easy and stable class 2 blocks, but the difficulty quickly increases to class 3 with some class 4 sections. Much of the climb also enjoys significant exposure and I find myself straddling long, airy drops several times. It’s difficult to describe the exact route, but we generally stick to the top of the ridge, occasionally dropping down a few feet on the right (west) side. Despite the scariness, the rock is incredibly solid and I enjoy the climbing!

As we approach the notch, I begin to look down the northeast face for cairns that match the routes I’ve seen described in trip reports but don’t see anything promising; the face is basically just a cliff. Jeff scouts ahead on top of the ridge and finds a rappel station just above the notch. Craig and I join him there and then all three of us rappel down about 40 m to a small bench that sits 10 m above the notch itself.

Once we’re all off rappel, Jeff pulls the rope and I lead the way down the final 30 feet on class 3 terrain. Partway down I hear Craig yell “ROCK!” and flatten myself against the cliff face just as a microwave-sized boulder explodes on the ledge a few feet away. I let Jeff and Craig lead the way after that. Our descent culminates in an exhilarating downclimb onto a chockstone suspended some 20 feet above the apex of two steeply descending chutes. From there, a few easy class 3 moves lead to a small ledge immediately below a long, angled slab.

Although the 160-foot slab is described as a class 4 climb, the exposure is high and a fall will likely have catastrophic consequences. So we put on rock shoes and rope up for the climb. Jeff, the most qualified climber among us, leads the way up the network of criss-crossing cracks, placing protection where he can (he reports most of the cracks flare outward) while I belay from below. The 50 m rope is just barely long enough to climb this route in a single pitch and Jeff belays from the top as Craig and I climb in tandem to join him.

The final few dozen feet to the summit consist of a mix of class 3 and class 4 climbing with a few highly exposed spots. Gandalf Peak itself proves to be a pretty tight spot, but we squeeze up there and revel in the accomplishment of climbing such a difficult peak! I’m also pretty stoked that we’ve reached our goal for the day by 12:30, four hours earlier than Craig and I managed yesterday. We sit for a while, munching on snacks and admiring the view.

On the way back, Jeff sets up a single-rope rappel for Craig and I which delivers us safely to the bottom of the ramp. Jeff rappels on a double strand (which only reaches halfway down) and then downclimbs the remaining 80 feet since there is no spot to build an intermediate rappel station. We once again cross the chockstone in the notch and scramble back up to the foot of our first rappel. The climbing directly up the face appears to be easy class 5, and Jeff once again takes the sharp end of the rope up to the rappel station. I’m glad for his confidence, skill, and calm manner on this climb; Craig and I both agree that he would make an excellent mountain guide. I really enjoy the climbing (on top rope, thanks to Jeff!) and soon top out on the ridge. Craig follows quickly behind me and then we pack up the rope, put away our rock shoes and harnesses, and prepare for the return journey along the ridgetop.

Now that we know the way along the ridge, we make slightly better time, arriving at Scimitar Pass by 14:30 (2 hr 15 min for the descent vs 2 hr 45 min for the ascent). The exposed climbing isn’t any easier, but at least we know which way to go. I’m happy to reach the relative safety of the class 2 boulders, even the loose ones. Downclimbing the 2000 feet of talus to Elinore Lake quickly becomes tedious however, and there are plenty of curses as boulders roll beneath our feet. We pass by Elinore Lake at about 16:50 and continue down the much easier, forested slopes. A series of cairns lead us along the south side of the creek through the woods, avoiding the long stretch of talus we crossed this morning.

We arrive back at camp around 18:30, tired and ready to be done for the day. The good news is that we get to follow a trail the rest of the way back and that requires much less mental energy than route finding. The bad news is that we have about 3.1 miles to go and over 2200 feet to descend. Jeff takes a short nap while Craig and I finish packing up the campsite.

The final three miles speed by, but it’s still dark by the time we reach the creek crossing below all of the switchbacks. I don’t want to break out my headlamp (I optimistically left it buried in my pack) and continue along in the dark, carefully avoiding rocks as I stride along the trail. But the near complete darkness in the woods surrounding the trailhead convinces Jeff to pull out a light to illuminate the final few tenths of a mile. We arrive back at the cars around 20:15 and sit for a little while, sipping on cold beers and comparing highlights from the trip. I’m proud of what we’ve accomplished but also so happy the suffering is over.

Craig Barlow 22 September 2021

What a weekend! I definitely won’t forget this one for awhile.

Jon 6 May 2022

Nice report, thanks for sharing!