I was scrolling through the Inyo National Forest Wilderness Permit website recently (as you do) and discovered a single permit available for the North Fork of Lone Pine Creek on Memorial Day weekend. I snatched it up, of course, and planned a hike to summit Mount Russell, a 14,088-foot peak just north of Mount Whitney. The climb to Mount Russell is more technical than Mount Whitney, featuring an exposed class 3 ridge. I was nervous about the route, but there’s really only one way to find out if I can do it: I have to go try.

Trip Planning

Specs: 8.7 mi | +/- 6000 ft | 1.25 day, 1 night

Difficulty: Class 3 with significant exposure on the east ridge [learn more]

Location: Inyo National Forest | Home of the Tubatulabal, Eastern Mono/Monache, and Western Shoshone peoples | View on Map

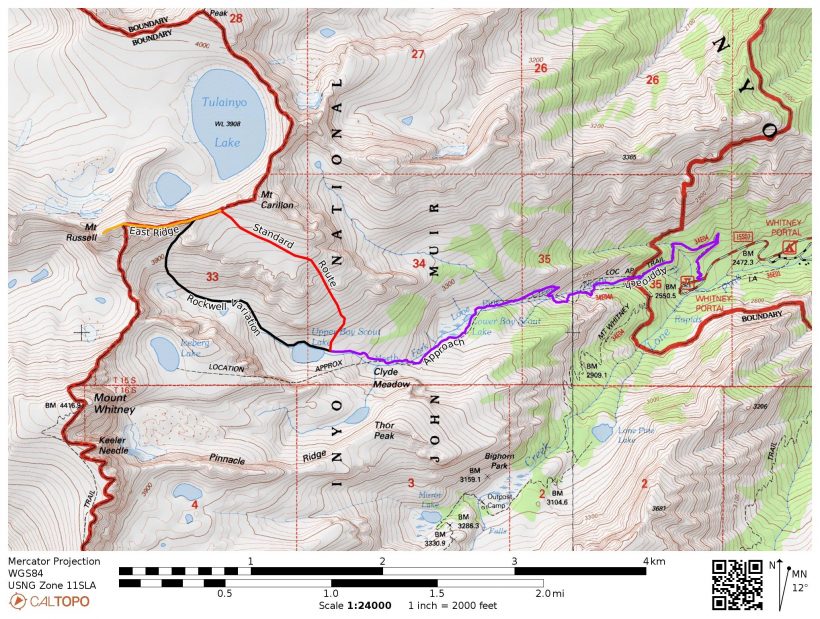

Route: The route is subdivided into several segments,

- Approach: Follow the Mount Whitney mountaineer’s route to Upper Boy Scout Lake. I recommend studying the description on SummitPost if you’re unfamiliar with this route.

- Rockwell Variation: From the foot of Upper Boy Scout Lake, traverse around the north side of the lake and follow the inlet creek up the valley, keeping the creek to your left. I found it simplest to stay relatively close to the creek rather than traverse across the talus and scree slopes above. After reaching a small tarn, continue up the valley until you reach the headwall; turn right and scramble up through loose sand and gravel to a chute that leads to the Russell-Carillon saddle.

- East Ridge: Carefully make your way up the ridge toward Mt Russell. Difficult segments can generally be bypassed on the right (north). This is a dangerous traverse. While not technically difficult (it is class 3), several sections are extremely exposed; a slip or fall could easily lead to serious injury or death. Only one day after I climbed this route, a man fell and died on the east ridge.

- Standard Route: A straightforward but extremely tedious alternative to the Rockwell Variation begins on the sandy slopes just below Upper Boy Scout Lake and climbs steadily uphill to a wide, shallow plateau that leads to the Russell-Carillon saddle. I would recommend descending via this route after ascending the Rockwell Variation.

Permits & Regulations: A permit is required for single-day and overnight use. For single-day trips, you’ll need a Mt. Whitney Zone Day Use Permit. Overnight trip permits are available via recreation.gov; select the North Fork of Lone Pine Creek (JM34) as your entry trailhead. You are required to pack out your solid waste in the Whitney Zone (the forest service provides wag bags) and bear cans are required if you’re staying overnight. For a full list of regulations, visit the Inyo National Forest website.

Resources: The SummitPost page has a great description of the route with pictures illustrating the key spots. The Mt. Whitney Facebook group has also been an invaluable source of recent trip reports and photos. I recommend the National Geographic topographic map of the Mt. Whitney area; Tom Harrison also publishes a nice map.

Portal to Summit

30 May, 2021 | 6 mi | +6000 / -3000 ft | View on Map

It’s 5 AM. After a fitful night of sleep at Whitney Portal interrupted by late-night returning hikers and early-morning departing hikers, I give up trying to rest and crawl out of my sleeping bag. I cook up a pot of oatmeal, repack my bag, and am on the Whitney Trail by 6:15. It’s a lovely morning with clear blue skies and not many people out hiking. A short distance up the trail I reach the junction for the North Fork of Lone Pine Creek and begin up the steep mountaineer’s path. Since the last time I hiked the mountaineer’s route, practically all of the snow has melted and I make good time through the woods, quickly navigating the Ebersbacher Ledges and subsequent switchbacks to Lower Boy Scout Lake. I pause there for a few minutes to stare out at the quiet meadow; what a beautiful place!

After a short rest, I continue up the mountaineer’s route, contouring around the lake and hopping across the talus slope that leads to Upper Boy Scout Lake. When I was here in early April, most of the area was covered in snow; Josh, Kim, and I kicked steps up this slope. Above the talus, I trek through willows and over granite slabs to Upper Boy Scout Lake, arriving at about 9:00 AM. This is a popular base camp for those climbing Mount Whitney and will be my home tonight as well.

Originally, my plan for today was to hike to Upper Boy Scout Lake and spend the rest of the day relaxing. But there are about 11 more hours of daylight and I don’t really fancy sitting around for that long. So I set up my tent, toss in all the gear I don’t need for the climb to Mount Russell, and head out. Several trip reports I read while preparing for this trip recommend following the “Rockwell Variation” to reach the Russell-Carillon saddle. It’s a slightly less obvious approach but (supposedly) passes through less loose sand and scree than the more standard route. I’m a little nervous about the Rockwell Variation; what if I climb up the wrong chute and get stuck in a difficult spot? My nervousness soon evaporates as I trudge up the sandy valley above Upper Boy Scout Lake and easily locate the chute up to the summit ridge.

I’m feeling a bit cocky at the base of the chute. Many trip reports bemoan the loose, sandy climb, but the approach thus far has been easy, even where sandy. As soon as I continue climbing, however, I discover that the chute itself is a slippery nightmare. With every step, I slide backwards. I resort to scrambling with my hands and feet, practically swimming up the steep slope. The 12,000+ foot altitude only increases the difficulty as I struggle to breath. I consider giving up and turning around at least a dozen times, but down-climbing the chute sounds even worse than continuing upwards so I wade on.

Thankfully, the ground firms up a bit higher in the chute. By the time I reach the Russell-Carillon saddle, my appetite is mostly gone, but I force myself to (slowly) eat some lunch. After a much-needed rest, I re-shoulder my backpack and begin scrambling up the intimidating east ridge of Mount Russell. The south side of the ridge is nearly vertical, dropping about 1000 feet to the valley I ascended during the approach. The north side is a little less steep and consists of inclined slabs interspersed with networks of ledges. I stick to the north side whenever possible, but the easiest path sometimes follows the very top of the ridge and I find myself carefully stepping beside that 1000-foot drop.

I choose the wrong route several times and have to backtrack to a safer line across the exposed ridge. Lingering snow and ice add a little extra challenge along the way, but I’m able to work around most of it. Thankfully, there is practically no wind today to push me around. I enjoy the climbing; there are plenty of large hand holds and even some fun ones like long, diagonal cracks and deep underclings. I’m careful to climb “statically”, moving from one stable position to another; an exposed ridge is no place for dynamic moves. (“Dynamic” climbing often involves big, energetic maneuvers like swinging from one hold to another or jumping through the air.)

About an hour after leaving the saddle, I reach the highest point on the ridge only to discover that a higher point lies a few hundred feet away. Cursing under my breath, I clamber down from the east summit of Mount Russell and continue my slow, careful climb to the higher western summit. I find the little register notebook and sign in and then sit for a while, admiring the expansive views. Mount Whitney looms large immediately south of Mount Russell; this is a perspective I haven’t seen before!

Dark clouds are gathering in the west, so I don’t sit too long on the exposed summit. It seems unlikely that they’ll bring rain or lightning, but I’m not eager to tempt fate this afternoon. The return journey along the east ridge takes a bit longer than the ascent; down-climbing the class 3 terrain is harder for me than climbing up it. By the time I reach the Russell-Carillon saddle, the clouds have thickened and are casting a dark shadow over Mount Whitney. Curiously, none of the clouds seem to be making it over the Sierra crest; they all stop above Whitney and then dissipate or drift south. I snap a few photos of the imposing peak and briefly contemplate scrambling up to Mount Carillon but decide to play it safe and continue descending in case those clouds bring rain, wind, or lightning over here.

I follow the standard approach route on the way down. In contrast to the Rockwell Variation, the entire route is covered in the loose gravel and I’m glad that I followed the more solid route for the uphill portion of the climb. Descending through the gravel is quite fun, though – I slip and slide down the hill, surfing my way back to Upper Boy Scout Lake.

I spend some time in the evening exploring around the lake and find Judy, Liz, and David — three fellow climbers I met at the trailhead last night — camped nearby. I sit and chat with them for a while before excusing myself to go to bed; it’s been a long day!

Leisurely Descent

31 May, 2021 | 2.7 mi | -3000 ft | View on Map

With Mount Russell in the bag, I lounge around camp in the morning, photographing the lake and enjoying existing at 12,000 feet above sea level. Once the golden hour light has cooled to the regular midday tone, I eat breakfast, pack up camp, and head out.

It’s another beautiful spring day and I’m in no hurry, so I pause a few times during the descent to admire the mountains and lakes. The hike out is really quite short, however, and it only takes me a few hours to reach the trailhead. This has been a great trip, and I can’t wait to get back up here and climb some more 14ers!

jojo 8 September 2024

Thanks! This helped me plan my ascent. Such a shame you need a whitney portal permit to do a seperate mountain. might just send it without one and risk the hundred fine.