Mountaineering is subtly ingrained in our collective imagination of outdoor adventure: a tough climber, decked out in winter gear, struggling up a steep, snow-covered slope toward the summit of some remote mountain. Through blogs like Tandem Trekking, I’ve vicariously struggled to some of the summits in the pacific northwest, but it wasn’t until last summer that I began to seriously contemplate trying out mountaineering myself. A few months after meeting some hiking buddies that were getting serious about a mountaineering course, I signed up for one myself: an introductory class taught on the slopes of Mount Baker, a glacier-clad peak near Seattle, Washington.

Trip Planning

Also called “alpinism,” mountaineering is generally the process of reaching the summit of a mountain. While some peaks (e.g., Mount Whitney) can be reached by hiking without any technical gear, most mountains are more rugged; reaching these summits can involve an approach hike, glacier travel, rock climbing, and/or ice climbing. To acquire some of these technical skills, I signed up for Alpinism I, an introductory mountaineering course offered by the American Alpine Institute (AAI). As such, I did not plan this trip myself, but rather followed the course guides, Seth and Kevin, as they led our group of 10 novice alpinists into the mountains. I would certainly recommend AAI; I learned a ton of new skills, had a great time in the mountains, and made a bunch of new friends!

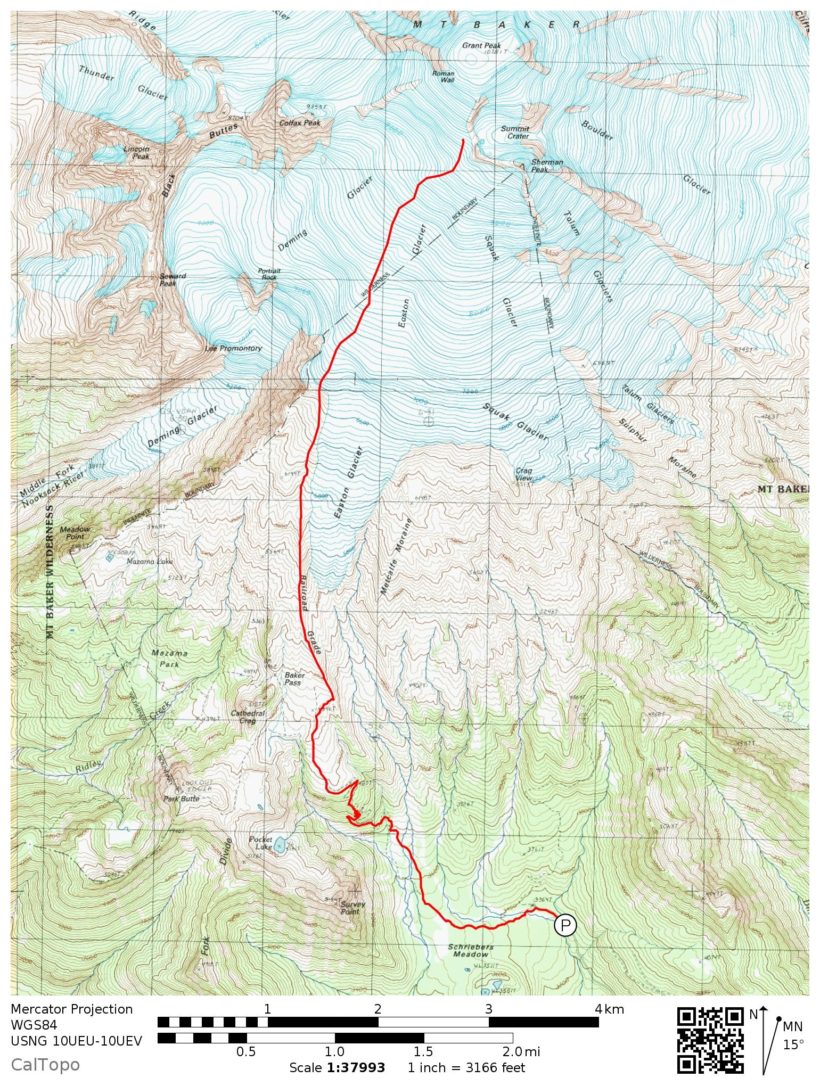

Specs: 14.4 mi | +/- 6700 ft | 6 days, 6 nights

Difficulty: Class 1, glacier walk [learn more]

Location: Mount Baker National Recreation Area | Home of the Nooksack, Coast Salish, and Nlaka’pamux peoples | View on Map

Route: We followed the Easton Glacier route, beginning at Park Butte Trailhead.

Permits and Regulations: Neither climbing permits nor backcountry permits are required for overnight trips in Mount Baker National Recreation Area, but a recreation pass is required to park at the trailhead and you should definitely register at a nearby ranger station in case of an emergency. For more information, please visit the forest service website. As always, observe the leave no trace ethics! In the wintertime, this means you’ll be pooping in a wag bag, certainly not a pleasant task but better than finding a minefield of turds on the mountain!

Resources: The USFS website is a great resource for planning trips in this area. Additionally, the AAI website includes sample itineraries and gear lists for their courses, a valuable resource whether you are considering signing up for such a course yourself or just want to get a feel for the gear and skills required. I brought along the Mount Baker Wilderness map printed by Green Trails (number 13SX), which has a great 1:24000 scale for a detailed view of the mountain and its many glaciers.

Rocks and Ropes

May 6, 2019 | Mount Erie

It’s a cool, sunny Monday morning in Bellington, Washington, the first day of the mountaineering course I’ve signed up for. I met a few of my fellow students this morning at breakfast; our trekking poles, ice axes, and large backpacks make it easy to identify each other. A cheerful AAI employee arrives just as we’re finishing our food and shuttles us over to the AAI facility where we meet the rest of the crew and our guides, Seth and Kevin.

The first order of business is to go through our gear together, under the watchful eye of the guides and AAI staff, to ensure that everyone has the appropriate supplies to be safe and comfortable in the mountains. After running through the gear list, many of us, myself included, rent some gear from the AAI shop and buy items that we’ve forgotten or could not bring from home.

A few hours later, the entire group is equipped, packed, and ready to go. We stuff our packs and other gear into the back of two large, black vans, and then depart for Mount Erie, a local crag. The drive from Bellingham takes about an hour and passes all kinds of different terrain: damp conifer forests, grassy meadows, vast bays, and a few picturesque lakes.

At Mount Erie, we tumble out of the vans and find a shady spot in a stand of pines to have “ground school,” i.e., learn some skills that we’ll need on the mountain from the relative comfort and safety of the warm, dry Washington coast. It’s pretty great place for a classroom; the views certainly beat any other classroom I’ve visited!

Seth and Kevin teach us about all things climbing: ropes, helmets, harnesses, carabiners, slings, and a variety of knots, hitches, and bends. It’s a lot to remember at first, but as we practice and discuss the context of each skill in mountaineering applications, they become easier to recall.

After learning the basics, we move to the crag and practice what we’ve learned. Half of the group learns how to climb a rope using a “Texas Kick,” a technique that leverages two prusiks and enables a climber to ascend the rope without touching the wall. It’s a beautifully simple system: one prusik (a thin cord tied in a loop) attaches to your harness at the waist and to the rope via a prusik hitch, and the other is tied to have two foot loops and is also attached to the rope via a prusik hitch. Basically, you stand on the foot loops, slide the waist prusik up the main rope, and then let your weight hang on the waist prusik while sliding the foot prusik up. Rinse, repeat, and up you go!

While some of us are practicing the Texas Kick, the other half of the group learns how to set up and perform an extended rappel with a prusik acting as a backup for the belay device. As a nerdy engineer, I find all of the new technical information and skills are terribly fun and interesting. We switch spots halfway through the afternoon so that everyone gets a chance to try both activities.

At the end of the day, we pack up our climbing gear and drive a short distance to Deception Pass State Park. I was a little confused about the name of the park at first since “pass” makes me think of a high-altitude saddle between two peaks. Deception Pass, on the other hand, is a very low-altitude saddle between two peaks; the pass itself is a narrow waterway. After driving around a few campsite loops, we find an open site with plenty of space for everyone and set up camp. To save space and weight in my pack, I’m sharing a tent with Madhav; we have to get a bit creative since the only stakes we have for the tent are the massive snow stakes, which won’t work in the rocky soil. We scavenge for rocks and end up with an awkwardly-pitched tent that won’t stand up to much wind but, thankfully, doesn’t need to tonight.

After eating some dinner, Madhav and I walk down to the shoreline and explore the park a little in the remaining daylight. It’s a beautiful place! We return to camp before dark and I head to bed right away; my body is still on eastern time, so 9 PM feels like midnight and I am pooped! Plus, I want to be rested and ready for tomorrow: our first day on Mount Baker!

Hike to Base Camp

May 7, 2019 | Mount Baker | 2.8 mi | +1600 / -200 ft | View on Map

An early bedtime means I wake up early. It’s already light outside, so I extract myself from my sleeping bag, put on some shoes, and step outside. Everyone else in camp seems to have a more normal sleep schedule, i.e., they’re all still asleep, so I decide to take a stroll. I find a trail nearby and wander down it to a beach that I glimpsed last night. The snow-capped Olympic Mountains are visible across the water, which laps quietly on the gravel beach. With plenty of time to kill, I meander further down the coast in search of a spot with views of Deception Pass.

After walking for a while, I return to camp, where more of the group is beginning to stir. I snack on a bagel, peanut butter, and dried mangoes, and then help Madhav pack up the tent. Once the whole group is packed and ready to go, we pile back into the vans and head out for Mount Baker.

The majority of the drive to the mountain follows paved roads, but the final few miles are a series of pot-holed switchbacks, which makes for a bumpy ride. We soon spot cars parked on the side of the road, a sure sign that we’re close to the trailhead. We don’t quite make it to the actual trailhead because the road is still covered in snow, a strange sight on a sunny, warm day like today.

Once Seth and Kevin have parked the vans we pull our gear out and prepare for a day of hiking. There are a number of group items to be distributed, including ropes, pickets, and shovels. I volunteer to carry a rope, which adds what feels like a solid 10 pounds to my pack weight. But carrying a rope does look cool, so there’s that.

As soon as everyone is geared up and ready to go, we begin hiking up the road toward the trailhead. The path is a mix of dirt and snow, which makes for an interesting experience in the mountaineering boots I’ve rented for this trip. They’re more or less the same as ski boots: a hard, plastic outer shell with little buckles protects a soft, inner liner boot. Anyone that has every clunked around in ski boots can imagine the awkward, uncomfortable experience of walking along a dirt road. Walking on the soft snow is more pleasant, but hardly comfortable.

I’m soon distracted from my unpleasant footwear by snowy forest scenery and the occasional glimpse of Mount Baker. Our group moves in a single file line through the snow, like a flock of geese. The person in the front of the line does the most work, sometimes sinking deep into the snow, but those of us that follow get to take advantage of their pre-compacted steps. We take a break every hour to munch on snacks, hydrate, and reapply sunscreen, a must-do with all the sunshine. The breaks are also a good chance to stretch out my hips, which have begun to ache from the heavy pack and the awkward boots.

Before long, we exit the forest and begin climbing up a wash between two ridges. Kevin, who is in front, warns us that we’re crossing over a creek (or creeks) here; the snow might be thinner and softer, but it’s hard to tell from above. The last thing anyone wants is to fall into an icy creek, so we tread carefully over the invisible snow bridges to one of the ridges. As we climb higher, expansive views of the surrounding peaks become visible.

We soon leave the gradually-sloping valley and begin climbing a series of switchbacks on a much steeper slope. The group spreads out a bit as everyone settles into different paces. We pause at the top of the ridge to regroup and watch as a few missteps create a tiny avalanche on the slope below.

After a brief rest, we continue down the other side of the ridge and make our way up gentler hills to a small valley surrounded by a few stands of pine trees. It’s a great campsite and it’s early evening, so we stop hiking and starting setting up camp. The first order of business is choosing a spot for the tent. Madhav and I stomp down a rectangle the size of our tent and wait a few minutes for the snow to re-freeze (a process called sintering or “work hardening”). Next, we set up the tent, digging dead-man anchors for the large snow stakes, and excavate a nice bench were can sit, cook, and stare at Mount Baker. Who knew snow camping could be so customizable?

After setting up the tent and unpacking a bit, it’s time for dinner. I boil water for a hot meal and then spend some time melting snow to replenish my water bottles. It’s not exactly a quick process with the little pocket-rocket stove I brought along, but the snow eventually liquefies.

I stay up long enough to watch the sun set; the views of the surrounding peaks are extraordinary, particularly in the warm evening light. Once the sun has sunk below the horizon, I retreat to the tent and crawl into my sleeping bag. I’m trying out a new system on this trip: a Therm-a-rest XTherm pad, one of the warmest available, and a sleeping bag liner that is designed to increase the insulation of the bag. Even though the tent is literally pitched on a slab of ice, I’m warm and cozy!

Snow School

May 8, 2019 | View on Map

Thanks to the warm tent and mild nighttime temperatures, I sleep soundly and wake up refreshed in the morning. I step out of the tent for a morning bathroom break, an experience made a little more… interesting by the snow. Normally you bury your waste so it can decompose, but that’s not very feasible when the ground is covered in deep snow. The solution is the “wag bag,” a fancy, opaque plastic bag with a zip-lock top. You simply poop in the bag, seal it up, and pack it out. Pooping in the bag isn’t so bad; carrying five days’ worth of poop off the mountain is.

After cooking and eating breakfast, we all gather at the base of a nearby slope for “snow school.” The first lesson is… walking. There are different techniques for ascending a slope, many of them with French names, all with different use cases; some are better for steep slopes, some are particularly useful when you’re wearing crampons. After learning and practicing the uphill techniques, we practice some skills for descending and then take a break. It’s surprisingly warm out; with bluebird skies overhead and a blanket of reflective snow covering every inch of the ground, there is no respite from the “death star” overhead. So, in addition to munching on snacks, I make sure to reapply sunscreen every hour or two.

The next skill that we practice is self-arrest, i.e., the process of stopping yourself from sliding/falling down a steep slope. In soft snow, it’s fairly straightforward to just dig your elbows and feet in to stop, but we’re also preparing for colder, icier conditions where an ice axe is the best tool for self-arrest. We learn about the parts of the axe: the sharp pick, the shovel-like adze, the shaft, and a sharp spike at the bottom of the shaft. The general idea behind self-arrest is simple: Stab the pick into the snow/ice, and kick your feet into the slope beneath you. Of course, there are some important considerations. Since self-arrest occurs after you’ve begun falling, you have to be very careful not to stab yourself with any of the pointy parts of the ice ax — control the ice axe. Seth and Kevin show us how to hold the axe, how to quickly position the axe relative to our bodies without injuring ourselves, and how to use the axe to swing our bodies into the correct orientation. To practice all of the skills, we form a couple of lines and take turns sliding down the slope, gathering a little speed, and then arresting the fall. It’s a little nerve-wracking at first (again, lots of sharp points involved!), but fun once I start to get the hang of the basic motions.

After lunch, we return to the hill and shift gears to anchor building. Anchors are systems that secure a rope in the snow; since there aren’t any trees or rocks to tie a rope to on a glacier, we have to learn how to use the snow to create a secure anchor. After Kevin and Seth teach us the basics, we split into pairs and practice. It’s tough work in the soft snow; Kevin is able to pull out the first several anchors my partner and I build, so they probably wouldn’t work too well if a climber were hanging off the end of the rope into a crevasse. The trick is to dig deep into the snow — at least two or three feet. That’s about as far as we can dig with the ice axe; they’re just not long enough to dig much deeper.

At the end of the afternoon, we transition to learning about glacier travel on a rope team. One of the risks while hiking across a snow-covered glacier is that someone will fall through the snow into a crevasse. This risk is mitigated by tying climbers together on a rope; if one person on the rope team falls, the others can self-arrest and stop their teammate from falling too far. We learn about coiling the rope, the knots used to tie in, and the appropriate amount of rope to leave between climbers.

We finish up in the early evening and walk the short distance back to camp. I have chores to do: melting snow to replenish my water supply, cooking dinner, and reviewing all of the new the skills I learned. To cap off a great day, the sunset puts on a colorful show on the clouds above Mount Baker. It’s much windier and feels colder than last night, but I stay up to photograph the sunset anyway; it’s not very often that I get to visit the Cascade Mountains!

Mountaineering Lessons

May 9, 2019 | 1.0 mi | +800 ft | View on Map

We pack up camp the next morning at 8 AM and begin a short hike to a location further up the mountain. We’ll wake up extra early tomorrow (an “alpine start”) and make a bid for the summit, which will be easier if we start a little closer to the mountain.

Soon after departing our first campsite, we reach the ridge-top path known as the “railroad grade.” This trail winds along the lateral moraine on the west side of the Easton Glacier and offers fantastic views of the surrounding scenery!

We abandon the railroad grade at a particularly steep, exposed spot, punch-stepping our way through the soft snow to a lower, flatter area. From there, we climb a few undulating ridges and reach Sandy Camp, a popular staging spot for climbers attempting to summit Mount Baker. Of course, there’s no sand to be seen; everything is pure, blinding white snow. Perhaps it’s a sandy spot later in the season.

Everyone scatters around the area, picking out nice campsites and setting up tents. Madhav and I choose a spot below the ridgeline where there will (hopefully) be less wind, even though the ridge-top spots offer amazing views. I figure I can walk the 50 yards to the ridge, check out the views, and then sleep in the relative comfort of the less-exposed tent.

Once camp is established, we resume snow school. The first lesson of the afternoon is crevasse rescue, i.e., the process of pulling someone out of a crevasse once they’ve fallen in. The techniques we’ve learned over the past few days all come together: knots, prusiks, self-arrest, and anchor-building are all key components of the crevasse rescue. It’s neat to connect everything together!

My favorite part of the afternoon is learning about and practicing building haul systems: we use carabiners and prusiks to construct a system of pulleys that effectively reduce the amount of force the rescuer must exert to pull their friend out of the crevasse. As an engineer and an aspiring mountaineer, I very much enjoy using the laws of physics to gain a mechanical advantage with materials I’m already carrying.

We split into a few groups and each practice the complete process of crevasse rescue, minus the anchor building. Seth, Kevin, and other group members take turns acting as victims, “hanging” on the end of the rope to give the system some tension and simulate a real scenario.

Later in the afternoon we also spend some time practicing rope team travel. It can be a little tricky: too much slack between climbers can be dangerous and get in the way, but too much tension ends up jerking everyone around as they adjust their speed with the terrain. We practice for a while, moving uphill, downhill, across flat areas, and around sharp corners.

We end our lessons at a reasonably early hour, eat dinner, and prepare for tomorrow. We’ll be leaving camp at 2 AM for our summit bid. Most of the hike is across a glacier so we’ll be roped up and will be moving more slowly than we might otherwise travel unencumbered by the rope. Of course, it’s better to move slowly than to fall to your death in a deep crevasse. With such an early start time, I head to bed soon after dinner; I won’t get enough sleep regardless, but I’ll take what I can get.

Summit Bid

May 10, 2019 | 5.8 mi | +4300 / -4300 ft | View on Map

After only a few hours of sleep, my alarm goes off at 12:45. Thankfully, we’re leaving most of our gear here at camp, so our packs will be relatively light. I stuff plenty of snacks, water, extra layers, and my camera into my backpack and pull on clothes. It’s not a terribly cold night, but the air is chilly, so I don a few layers and munch on a cliff bar. Before staring, Kevin and Seth suggest that we “be bold, start cold,” i.e., we should take off a few layers before starting the climb. Following their advice requires a bit of a leap of faith (it is quite chilly), but turns out to be a good policy. As we trudge up the mountain in a single file line, I warm up and am comfortable.

Upon reaching the edge of the glacier, we pause and rope up into two teams of six: one guide and 5 students on rope. Our headlamps light the way as we trek up the glacier, but we don’t need them for as long as I expected. Around 4:00, the sky begins to brighten, and by 4:30 there is enough ambient light to see without the lamp.

When the sun does rise above the horizon, the view becomes spectacular. Seeing alpenglow on one peak is great, but seeing alpenglow on every peak for miles and miles is amazing!

Even though the sun has risen, we’re still in the mountain’s shadow, crunching up the icy snow in our crampons. As I climb, I begin to notice a sharp pain in my shins, right where the tops of the boots press against my legs. I’m able to walk through it for a while, distracted by the epic views, but am soon grimacing with each step. I try loosening the boots, tightening the boots, and adjusting my socks, but nothing makes much of a difference. Those tweaks may have prevented the pain if I applied them earlier, but my shins are bruised and tender, so my only choice is to keep walking; the summit awaits!

The sun rises as we near the summit crater, and other mountaineers begin passing us, many of them on skis. Watching them glide up the mountain makes me a little jealous – it looks so effortless! I’m sure it isn’t actually effortless, but the real kicker is watching some of them fly past us on their way down; they’ll reach the bottom in an hour, whereas we’re going to have to walk for five or six hours.

About once an hour we take a break to refuel, rehydrate, and rest. During the breaks, I pull my camera out of my backpack and snap photos. Pausing for photos mid-climb isn’t an option since I’m tied to several other people; everyone on the team would have to stop, and we’re on the clock. The glacier becomes more dangerous as the temperature rises. Snow bridges (i.e., the sheets of snow covering the gaping crevasses somewhere below our feet) that are sturdy when frozen can become weak when the snow thaws, and moving through wet, soft snow is much more tiring and difficult than moving along the icy crust.

By the time 9:30 rolls around, we’re a little shy of the summit crater and several miles away from the summit. We’re out of time. We push on a little further to get a glimpse of the crater, but soft, deep snow near the rim prevents us from looking inside. Mount Baker is an active volcano, as illustrated by the sulfur-laden fumes spewing from the crater. The aroma isn’t as strong as, say, Yellowstone’s mudpots, the air smells distinctly of rotten eggs.

We rest for a few minutes near the crater and admire the panoramic vista. I’m disappointed that we haven’t made it to the summit, but this is a team sport: either everyone makes it, or nobody does. Besides, making the difficult decision to turn back is a valuable mountain lesson, one that I’m still learning. We could continue up to the summit, probably arriving around noon, 10 hours after leaving camp this morning. Then we would have to hike all the way back to camp, which would take several more hours and would occur during the hottest part of the day. Everyone would be exhausted, and we would need to be extra careful to avoid stepping through a soft snow bridge. Tiredness and deteriorating conditions are a recipe for an accident, so we’re turning around. The mountain will remain; I’ll just have to come back!

Descending the mountain is much less painful on my shins, thank the gods, but still a measured, slow ordeal. The sun is hot, the snow is soft, everyone is tired, and emotions are a bit rough. Bear steps through a snow bridge in a spot we walked safely this morning, illustrating just how quickly conditions can change on the mountain. Thankfully, only his leg falls through; his rope teammates are easily able to pull him out by moving sideways as a group.

Other than that small excitement, the descent proceeds uneventfully. We take off the crampons once we reach consistently softer snow, and post-hole our way down the glacier. Once we reach the lateral moraine, we untie from the rope and continue along the ridgeline to our campsite. The snow at these lower elevations is incredibly soft, and I find myself sinking up to my knees as I trudge downhill. At one point, Mike sinks up to his hip and John and I have to dig him out!

Upon returning to camp, we debrief with Seth and Kevin, discussing the climb and some of the things we learned. Afterward, we all take some time to rest. I pour melted snow out of my boots, set them out to dry in the fierce afternoon sunlight, and lie down. I’m too tired to stay awake, so I set an alarm for 19:30 and then go to sleep. When the alarm goes off, I get up and spend an hour admiring the sunset before returning to bed for the night.

Retreat

May 11, 2019 | 3.8 mi | +200 / -2400 ft | View on Map

Today is our last day on Mount Baker, and the last day of the course. We pack up camp in the morning and then spend a few hours practicing crevasse rescue techniques. It’s another warm, sunny day, and everyone seems a bit more cheerful after a full night’s rest. I take a turn being the “victim” to be rescued; it’s pretty fun to lean back against the rope and watch someone build a set of pulleys to pull you out of a fictional crevasse.

Once everyone that wants to has practiced the rescue skills, we begin hiking out, retracing our steps from earlier in the week. We walk past our first campsite and soon reach the steep ridge that we criss-crossed with switchbacks on Tuesday. Rather than repeat that ordeal, Kevin and Seth make the executive decision that we will be glissading down the slope. It’s a tad steep, but the bottom is smooth and clean, a perfect spot for some good old butt-sliding.

As we descend further, we reach the valley with several streams. Unlike our ascent a few days ago when the streams were completely covered by snow, there are now some holes above the creeks. Step carefully near the water to avoid punching through, we continue downhill. The further we go, the greater the evidence of melting. All sorts of things that were previously hidden now protrude from the snow: rocks, trees, logs… Walking through this minefield is a little tricky — post-holing is no fun — but we eventually reach the vans. I’m particularly happy to trade my boots and heavy pack for trail runners and a fresh shirt.

On the drive home, we stop at a small gas station and buy some treats: Gatorade, ice cream, chips… the good stuff. Back at the AAI shop, I return the gear I rented and say goodbye to everyone. It’s been a great week, and I’ve learned so many new skills! I can’t wait to do more mountaineering, and perhaps return to Mount Baker — gotta bag that summit!