A recent business trip for a conference brought me and several of my friends to Maui. Naturally, we stuck around for a few days after the conference to snorkel, watch whales, sip cocktails on the beach, drive the Road to Hāna, and hike! I was most excited to explore the summit district in Haleakalā National Park, a desolate, volcanic wilderness located at the summit of the 10,000-foot Haleakalā volcano, so Brian, Diane, and I spent an entire day hiking through the area.

Trip Planning

Specs: 16.3 mi | +/- 3700′

Difficulty: Class 1 [learn more]

Location: Haleakalā National Park | View on Map

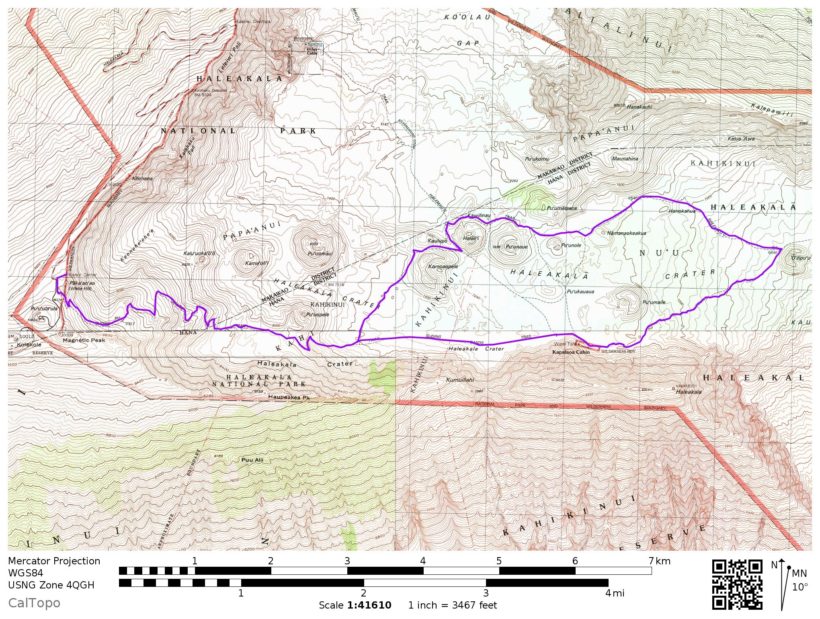

Route – Park at the Pā Ka’oao (White Hill) visitor center; the Keonehe’ehe’e (Sliding Sands) trail begins at the southeast corner of the parking lot. Follow the Keonehe’ehe’e trail down into the Haleakala Wilderness area. Once on the valley floor, you have plenty of trails to choose from and can string them together to form loops of various lengths. My friends and I hiked to the junction just west of ‘Oilipu’u and then returned along the Halemau’u trail. Be warned: you have to climb 2,500 feet from the valley floor back to the summit to return to your car (at nearly 10,000’). Give yourself plenty of time to complete these strenuous final miles.

Permits & Regulations – No permits are needed for day hiking, but overnight trips require a permit. As always, follow leave no trace principles: pack out your trash (this includes toilet paper)!

Resources – The national park website is a great resource with lots of information; that should be your first stop to learn about the park. For navigation, I recommend the National Geographic topographic map which includes the locations of all campsites and trail mileages.

A Volcanic Wilderness

19 Jan., 2019 | 16.3 mi | +/- 3700 ft | View on Map

The United States government is not currently funded. During previous “government shutdowns,” the national parks have closed to the public; without any funding to clean the restrooms or protect visitors’ safety, it’s easy to see why. For whatever reason, this shutdown is different and Haleakalā National Park remains open, albeit unstaffed. A single ranger is restocking the restrooms at the Pā Ka’oao visitor center when Diane, Brian, and I arrive. The chilly air on the 10,000-foot summit is a dramatic change from the warm, sunny Maui beaches where we’ve spent the past several days. Thankfully, it’s also super sunny on the mountain, not raining or storming like the weather forecast for today has been predicting. Of course, it may rain or storm on the island below… we seem to be several thousand feet above the clouds up here!

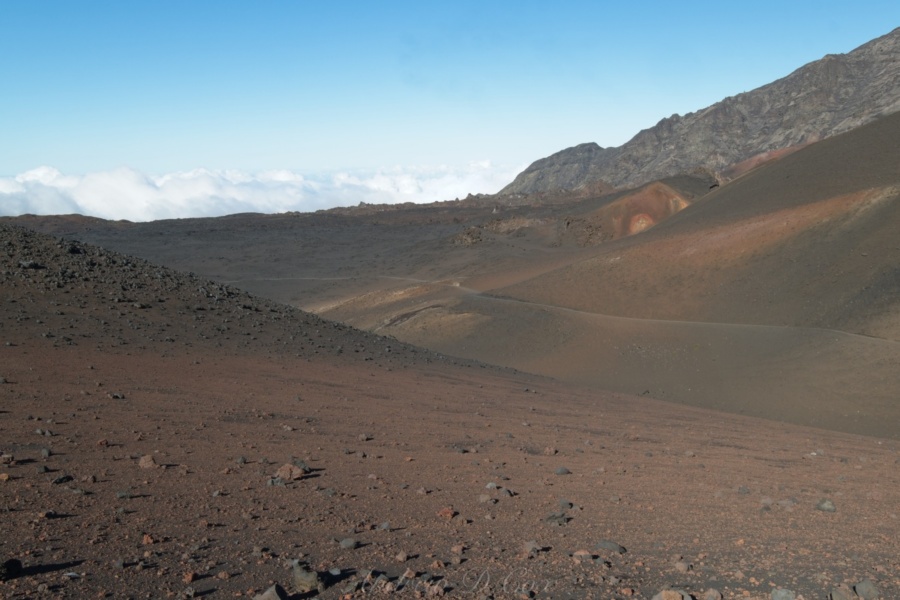

After admiring the views from the Pu’u Ula’ula overlook, we shoulder our backpacks and locate the Keonehe’ehe’e (Sliding Sands) trailhead at the southern corner of the Pā Ka’oao visitor center parking lot. The sandy trail winds around a small hill and then reaches the edge of the “crater.” The massive valley isn’t really a crater – Haleakalā didn’t blow its top off like St. Helens – but the desolate, lava-filled landscape certainly looks like a crater. A few other hikers are winding their way down the trail below us, tiny compared to the vast landscape. We admire the views for a moment or two and then begin our own descent.

Despite its nickname, the “sliding sands” trail is very stable and easy to speed down. Ribbons of red, orange, and dark gray sand form large, sweeping curves below the trail, giving the illusion of motion. We descend lower into the valley and the sun climbs higher in the sky; wearing a jacket becomes uncomfortable so we stuff them into our packs. Further down the trail, we run into a few friends and hike with them to a rocky overlook with nice views of the colorful valley.

While the valley is certainly dominated by sand and stone, there are plenty of hearty plants living their lives here. The Haleakalā Silversword is the most famous; this yucca-like plant is endemic to the Hawaiian islands (it grows nowhere else) and can live for up to 90 years! At the end of its life, the silversword produces a tall column of flowers, the seeds of which are soon scattered by the wind. We spot plenty of silversword plants along the way, but none in bloom.

The descent to the valley floor takes several hours to complete. From the trailhead this morning, the drop didn’t look all that large, but a glance at the map reveals that the valley is over 2,500 feet lower than the visitor center! In the back of our minds we’re all aware that we’ll have to climb up that slope on the way back, but for now there are too many exciting things to see and explore!

Around noon, we stop for lunch in the shade of a large bush. Although I’m very warm from the hours of hiking to this point, the shade proves chilly, a reminder that we’re still far above sea level. We all enjoy grocery store sandwiches and some more indulgent snacks; Brian has a bag of animal crackers, Diane has a bag of Nutter Butters, and I packed chocolate covered raisins. There’s nothing like hiking all day to earn some high-calorie treats!

After lunch, we continue along the trail, working further into the valley. We stride through fields of dead ferns and prickly grass for a while, with the valley’s southern walls nearby on our right. There seems to be some water dripping down those steep slopes, but it doesn’t reach the trail or any of the thousands of dead ferns. At some point that moisture must flow down here, though, otherwise there wouldn’t be so many plants.

A little further down the trail, we reach the Kapalaoa Cabin, with luxurious amenities like running water provided by a tank tucked into the slope above. The cabin is locked, but the outhouse is open! After using the facilities, we debate about whether to continue down the trail or turn back. There is supposed to be a north-south trail here that links up with trails on the other side of the valley; ideally, we would like to return on that side to see some different scenery. However, the link trail is nowhere to be seen and we’re about half-way through our allotted hiking time (we have a flight deadline to meet). Further complicating the decision, the valley ahead of us is covered in mist and promises new and exciting scenery…

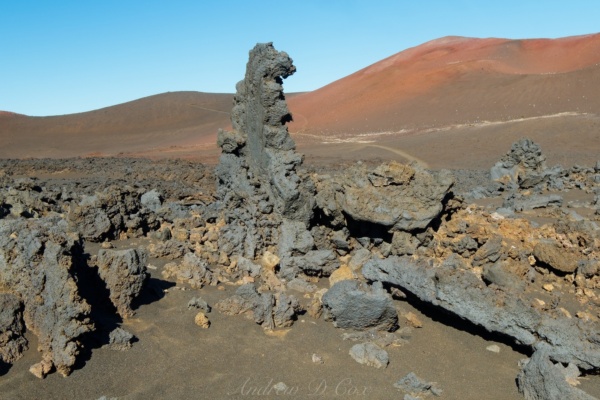

As retracing our steps is the least attractive option, we decide to continue down the valley, just a little further. Past the cabin, the wide, flat, gravel trail transitions into a winding, twisting path between massive piles of twisted lava rock. A short while later, we reach a flatter plain of the dark rock interspersed with bright green bushes. The icing on the cake is a view of Mauna Kea, a volcano on Hawaii, poking through the sea of clouds. By this time, we’ve talked ourselves into hiking to the next junction, even if it does mean we cut our evening deadline a little close.

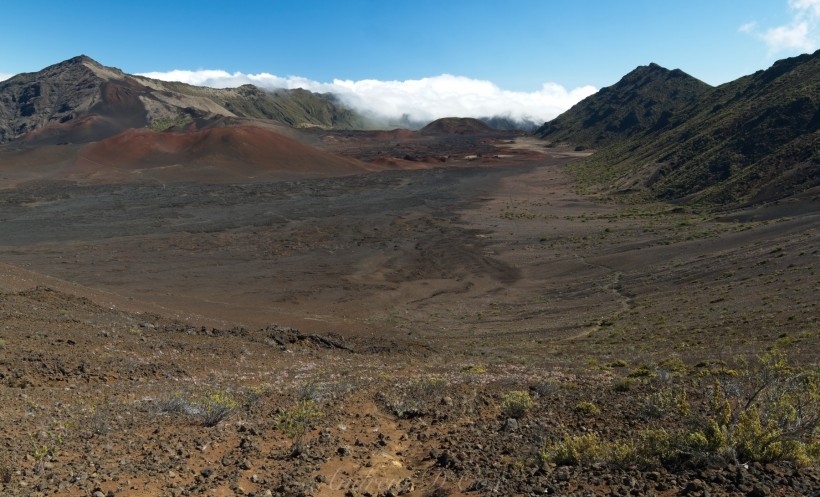

I think I speak for all three of us when I say that hurrying to fit in a few extra miles to reach the Halemau’u Trail at ‘O’ilipu’u is worth the effort. Here on the eastern side of the valley, clouds flow up and over the mountains walls, bringing much-needed moisture. The ground is practically spongy, a stark contrast to the sharp, twisted lava flows just a few hundred yards away.

From the junction, we follow the Halemau’u Trail east, back toward the trailhead some 8 miles distant. The lush vegetation continues for a while, and we even hear birds chirping in the scrubby trees! A pair of Nēnē startle as we wind up a small hill, honking as they fly away. These Hawaiian geese look remarkably like Canadian geese even though the Nēnē is endemic to the Hawaiian islands.

Perhaps my favorite sight of the hike is the juxtaposition of a “new” lava flow, characterized by barren, naked, black rock, with the grassy, heavily-vegetated earth nearby. How much younger is the lava flow than the surrounding land? 10,000 years younger? 100,000 years? It’s incredible that we can see such a stark contrast between the two. As none of us are geologists, we continue up the trail without any answers to these questions.

Further up the valley, the vegetation gives way to truly desolate wilderness. A few tiny tufts of grass dot the sandy slopes of the cinder cones that once spewed lava into the valley, but that’s all the life we can see. Between two of these cinder cones, we pass a deep pit encircled in wire fencing; a sign declares that this “bottomless pit” is 65 feet deep… seems a tad shallow for “bottomless.”

A little later, we reach an area with incredibly colorful sand nicknamed “Pele’s Paint Pot.” With red, purple, orange, and yellow sand streaked across the cinder cone slopes, the name fits. As we wind between the cones, we’re afforded a few of the visitor center perched high above the valley, glittering in the late afternoon sun. It looks so far away, but experience tells me that a few hours of walking is all it takes to cover the distance.

The trail continues to twist and turn between the numerous sandy cones, eventually descending into a large valley full of strange, twisted rocks. It looks very alien; Mars-like, perhaps. The lava doesn’t even look solid, like some strange extrusion from a 3D printer. The path makes a beeline through these curious formations; I pause a few times to examine them more closely and then hurry to catch up with Brian and Diane.

At last, we reach the bush where we ate lunch, a sign that it’s time to begin climbing. Although the trail isn’t particularly steep, the ascent is long and difficult. The vertical difference of 2,500 feet is nothing to be scoffed at, particularly after already hiking 12+ miles. The thinning air as we climb to 10,000 feet only adds to the struggle.

The sun dips below the valley rim during our climb, casting long shadows across the volcanic landscape. Curiously, we pass a fair number of people descending into the valley as we climb out. One couple, dressed in t-shirts and blue jeans, naively asks for directions to Pele’s Paint Pot. Since they don’t seem at all prepared to night-hike, I mumble something about being able to see colorful sand from a nearby switchback and continue trudging toward the top.

As luck would have it, Brian, Diane, and I reach the top of the mountain just as the sun is setting. We delay our departure for a few minutes to watch the show, shivering in the cold mountain air. As soon as the sun has dipped below the clouds, we race back to the car drive back down the mountain, leaving the strange volcanic wilderness behind