15 August, 2015 | Spruce Knob, West Virginia | Home of the Shawnee people

As a photographer and a person interested in space, I wanted to watch the Perseid meteor shower this week. However, I’m currently situated near Washington DC, which has horrendous light pollution. The sky doesn’t turn black at night, it turns orange. If you’re lucky and there aren’t any clouds, you can usually see a handful of stars, but that doesn’t really cut it.

Choosing a Location for Astrophotography

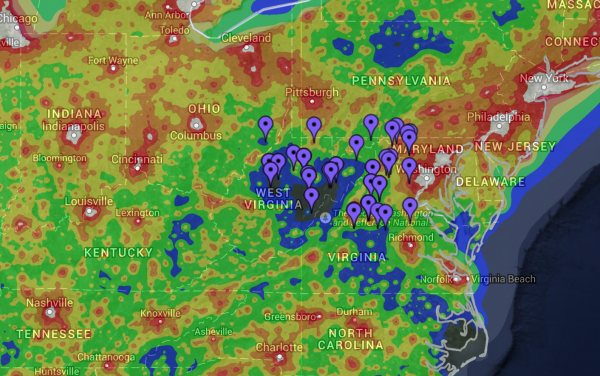

To remedy this situation, I pulled up Dark Sky Finder, a map that shows light pollution in the United States, and looked for areas nearby that have low light pollution. As you can see from the map below, DC has a high amount of light pollution (white, red, and orange colors). However, about 140 miles to the West is an area with very little light pollution! I did some research and found a mountain called Spruce Knob in this dark sky region. I wish I had discovered it sooner because it looks like it has lots of nice hiking trails and back-country camping! To make the area even more appealing, Spruce Knob is described as having “an alpine look and appeal,” unlike other peaks in the Appalachians. I suppose I’ll have to add it to the list of places to explore in the future. In the meantime, I’m going to spend a night on this alpine peak to watch the meteor shower and photograph the stars.

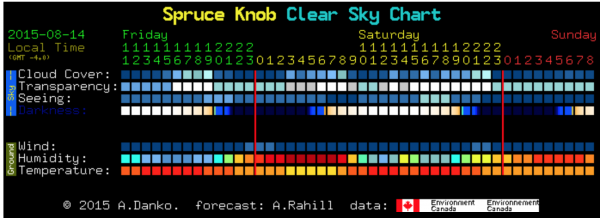

In the days leading up to the trip, I checked the astronomy weather forecast several times to make sure the conditions would be good. There is a new moon this weekend, so the sky will be as dark as it possibly can be. There are supposed to be very few clouds and little wind, although the relative humidity is forecast to be high. High humidity can make the atmosphere more opaque and can also fog up the camera lens; I have hand warmers for the lens to prevent fogging, but there’s not much I can do about the atmosphere.

I left DC on Friday evening at about 6:00, hoping to be late enough to avoid some of the traffic congestion. People leave work early on Fridays, right? Wrong. In the first hour, I made it maybe 20 miles and reached Alexandria, VA. After that, the trip goes quickly. Driving through rural West Virginia at night is a lot of fun. Many of the roads have steeply banked curves and you don’t have to slow down too much from the 55 mph speed limit… By the time I reach Spruce Knob, it’s already dark. I’m a bit sleepy from the 4.5-hour drive and I wonder if I’m going to be able to stay up to take pictures. I unpeel myself from the driver’s seat, step out of the car, look up – and the tiredness instantly melts away.

There are millions of stars in the sky, and the Milky Way is clearly visible. Humans don’t see much color in low light situations like this, so I can’t make out the colors of the stars, but I know my camera will be able to. I grab it and my lenses from the car and then set about locating a trail that will take me to the overlook tower. I have a headlamp to light the way and after a few minutes of searching, I find the trail and walk about 1/8 of a mile to the overlook. There are several other people already atop the tower, including a few photographers.

Camera Configuration

Once I have my camera (a Nikon d7100) set up and pointed towards the Milky Way (which I can see plainly with my eyes… incredible!), I take a few test shots to get the composition right. To make this go quickly, I set the ISO to something stupidly high like 64,000 or 128,000 and use a short exposure time. The resulting image shows the stars and gas clouds of the galaxy and how they are positioned relative to the trees and other foreground elements. The image noise is ridiculous, of course, but these are just test shots to make sure that the frame includes mostly stars with a few trees and hills below.

Before doing anything else, I need to make sure the camera is as still as possible (a shaky camera is just as bad as an out of focus camera), so I pull out an infrared remote control. I’ve found that using the remote mirror-up setting works best: the first click of the remote raises the mirror (which makes the camera vibrate) and the second click opens the shutter (which causes much less vibration). As long as I wait a second or two between the first and second click, the camera will stay as still as possible. Having a heavy, sturdy tripod would help a lot too, but I don’t have one right now and have to make do with my little Joby Gorillapod.

The next step is to set the focus. I’m using a Tokina 11-16mm f/2.8 lens, which is plenty fast for astrophotography, but it still can’t autofocus on the stars. I can’t even see any stars looking through the viewfinder; I think the blinking display ruins any night vision I might have looking through the camera. So, I have to actually take a picture and then review it on the LCD screen to see if the camera is in focus. While still keeping the ISO high and shutter time low, I take a picture and then zoom in on one of the stars. If it is a small point of light, the picture is in focus. If the star appears to have lobes or is less bright in the center than the edges, the picture is out of focus. It takes several shots, and I eventually get the shot as focused as I can. I keep the lens set on manual focus so the camera won’t try to adjust the focus.

My final consideration is the exposure. I set the aperture to f/2.8, as wide as it will go to let in as much light as possible. Exposure time is limited by the Earth’s rotation: if I keep the shutter open for too long, the stars will start to smear across the image, creating “star trails.” Although those images can be cool, it’s not the look I’m going for. My rule of thumb is to divide 400 by the focal length of the lens multiplied by 1.5 (the crop factor for my camera). If I use the 11mm end of the lens, I should be able to leave the shutter open for about 25 seconds before the stars will appear to move. I experiment a bit and find that the stars look like they’re moving anyway, so I try shorter exposure times. Fifteen seconds seems to do the trick. Finally, I adjust the ISO to create a properly exposed shot. This isn’t by any means an exact science. An ISO of 1600 will show the stars pretty well with little noise, but an ISO of 3200 will expose the dust clouds in the Milky Way a bit better at the expense of higher noise.

Miscellaneous settings:

- Image Stabilization: Off (lens doesn’t have it)

- High ISO Noise Reduction: Off

- Long Exposure Noise Reduction: Off

- Active D-Lighting: Off

- White Balance: Set to something other than Auto, will correct in post

- Image type: RAW 14-bit, Uncompressed

Once the camera is set up, I sit back and start taking photos. It’s really exciting to see the camera return image after image of the beautiful Milky Way. I spend a lot of time looking up while the camera does its thing. There are a fair number of meteors streaking across the sky, although they tend to avoid appearing in any spot I point the camera at. I stay out for several hours… it’s wonderfully still and quiet up on the lookout tower, and the view simply can’t be beaten.

FabioB 9 December 2015

so the Joby Gorillapod is stable and secure to shot with long exposures and for the astrophotography?!

I would buy a Gorillapod FOCUS, but I’m undecided, whereas above it I would mount a Canon 6D with Tokina 16-28mm 2.8…

Andrew 9 December 2015

With care, yes, the Gorillapod is capable of staying perfectly still. I found that I had to use the mirror up remote shutter release to keep it still – the mirror’s motion is enough to give it a shimmy on the Gorillapod.